Community Seed Banks in Zimbabwe: A Lifeline for Farmers Facing Climate Change

In Zimbabwe’s Mudzi district, community seed banks are emerging as essential tools aiding farmers in coping with rampant climate challenges and drought conditions. Established as part of efforts to bolster agricultural resilience, these banks allow locals to access drought-resistant seeds at no cost and empower them through local ownership. Despite initial skepticism, heightened demand and support for these initiatives indicate promising shifts towards self-reliance and enhanced food security in the region.

In Zimbabwe’s Mudzi district, where dry conditions are a way of life, community seed banks are emerging as a vital resource for farmers grappling with increasingly erratic weather patterns. Last year, devastating drought conditions, described as the “worst in living memory,” caused significant crop losses, leading to heightened food insecurity across the region. The impact of climate change, notably accelerated by phenomena such as El Niño, has led to over 68 million people in southern Africa requiring food assistance, significantly affecting Zimbabwe’s farming communities.

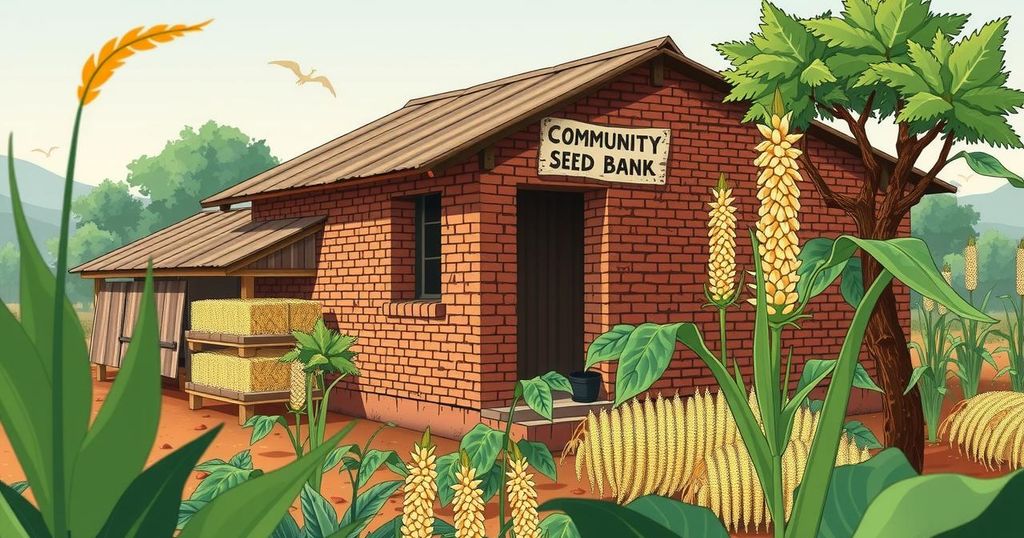

Amid these challenges, the Chimukoko village offers hope. Locals can collect drought-resistant seeds for crops like sorghum and millet at no cost from their community seed bank, or bhengi re mbeu, established in 2017. This initiative aligns with global efforts to bolster agricultural resilience in the face of climate change threats. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that crop yields in southern Africa could decline by up to 60 percent in the coming decades.

One aspect of the Chimukoko seed bank’s success lies in its ability to preserve traditional agricultural knowledge. It contains around 20 different varieties of seeds to encourage a diversified farming approach, which stands in stark contrast to the prevalent reliance on corn monocropping—a practice rooted in colonial agricultural policies. Andrew Mushita, an agronomist and director of the Community Technology Development Trust (CTDT), emphasizes the importance of local ownership in this endeavor: “These materials are quite key in terms of empowering local communities to produce and own the means of production.”

The seed banks help smallholder farmers cultivate crops that are not just resilient but culturally appropriate for their communities. This local approach empowers farmers to respond quickly when their planted crops fail, allowing them to take seeds from the bank to plant anew—especially critical during times of drought when consistency in planting is vital for survival. Ronnie Vernooy, a rural development expert, points out that growing a variety of crops decreases vulnerability to disasters such as drought.

However, community seed banks initially faced skepticism from formal agricultural institutions. Vernooy notes that these organizations believed only highly educated conservationists could manage such initiatives. Yet, attitudes have shifted, and support for community seed banks has increased globally. The Alliance of Biodiversity International, along with CIAT—where Vernooy works—has made community seed banking essential to their mission, positively influencing many nations since 2011.

The roots of seed banking trace back to ancient times, but contemporary community seed banks boomed after the Ethiopian famine in the mid-1980s. They aim to increase autonomy among local farmers and reduce reliance on broader food supply chains. In Zimbabwe, however, the concept rose slowly, facing pushback initially when the CTDT aimed to promote indigenous seeds over hybrid crops.

Over time, more farmers embraced the seed bank’s benefits. Since the Mudzi facility’s opening, 26 additional seed banks have emerged across Zimbabwe, with plans for more. The organization works closely with local communities, making education around seed bank benefits a priority. From land acquisition to construction, local input is paramount in establishing these banks. Farmers elect committees to manage seed distributions, providing accountability and fostering a sense of ownership throughout the community.

Currently, the government seems to be taking a supportive stance, as officials like Deputy Minister Vangelis Haritatos have acknowledged smallholder farmers’ crucial roles. Still, legal barriers exist, complicating formal registrations of these banks. The CTDT is striving to create a nationwide policy to formally integrate community seed banks into Zimbabwean agricultural practice. This proposed policy could bolster self-reliance and facilitate technical assistance through local agricultural extensions.

Mushita observes that as communities engage with seed banks, they begin to grow various crops. Though data on food security impacts remains sparse, personal observations suggest communities utilizing these banks are more resilient to climate incidents. Moreover, successes in Malawi indicate that similar methods could boost food security, suggesting the potential for community seed banks to make lasting impacts.

At an international level, seed banks like ICRISAT work synergetically with community resources to enhance drought-resistant varieties, helping ensure food security far beyond local borders. Even though community seed banks often operate with limited resources, the collaboration with larger entities allows for the breeding of crops that can adapt to changing climates.

In a nutshell, seed banks like those in Mudzi are more than storage facilities—they are seeds of hope for resilient agriculture in challenging climates, essential for Zimbabwe’s agricultural future. As farmers realize the importance of diverse crop cultivation, these initiatives will likely play an increasingly vital role as the world continues to confront the pressing realities of climate change.

The emergence of community seed banks in Zimbabwe represents a grassroots effort to build resilience against climate-driven challenges in agriculture. These seed banks not only provide immediate support to farmers affected by unpredictable weather conditions but also empower them to regain control over their agricultural practices. By fostering biodiversity and encouraging local ownership, these initiatives hold potential for improving food security and preserving cultural agricultural practices in a changing world. As both local and governmental support grows, the future appears bright for these vital community resources.

Original Source: www.newzimbabwe.com

Post Comment